Tucson, Arizona – November 2015

“Sentencing” by Lawrence Gipe, ca. 2012-2014

“Sentencing” by Lawrence Gipe, ca. 2012-2014

Sixty two detainees, migrants from Mexico and Central America caught crossing the border illegally, sit in the large courtroom facing the judge. On his right is an interpreter. Our BorderLinks contingent sits in back to witness the proceedings, to keep the system “honest.”

The judge asks the group, “Do you understand why you are here?” “Do you understand the charges against you?” “Have you had an opportunity to talk with your attorney?” The defendants are instructed to stand if they don’t comprehend. No one stands.

The judge calls out names, stumbling over pronunciations. Five men, one woman, and their lawyers stand before him. Each is charged with a felony and has the option to plea to a misdemeanor and waive trial. One by one, the judge recites a litany to this effect. One by one, they plead guilty to the misdemeanor, waiving their right to trial, and are given sentences of up to 180 days.

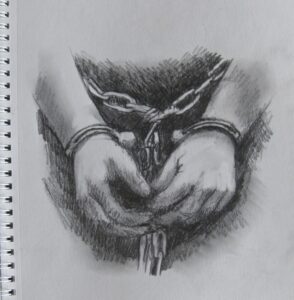

“Shackled” by Lawrence Gipe ca. 2012-2014

“Shackled” by Lawrence Gipe ca. 2012-2014

I’m struck by the politeness between the judge and the accused. Many answer his questions, “Si, senior.” The judge always finishes with, “Thank you for your time, and good luc.” The convicted often reply, “Gracias.”

Six human beings processed in less than ten minutes: First Appearance, Arraignment, Plea Bargaining, Sentencing. Very streamlined, very efficient. Is this American justice?

The convicted pass by us as they’re taken from the courtroom, looking resigned. Do they see empathy in our faces? Or only a sea of white faces, curious and judgmental?

All are handcuffed and shackled. What threat do these Mexican peasants pose? They’re accused of illegal border crossings, not dangerous crimes. All wear clothes they were arrested in, some cleaner than others, depending on how long they’d been in the desert and in jail.

The scene repeats itself. One man on crutches, legs shackled, is handcuffed to his crutches. Did he walked through the desert on crutches? Stories abound of Border Patrol officers abusing migrants, sometimes getting away with murder. Other stories tell of Border Patrol humanitarians who save lives.

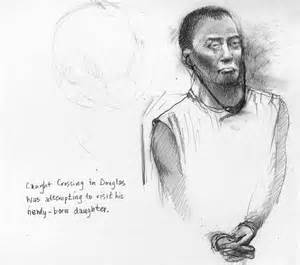

“Caught visiting his newly-born daughter”, by Lawrence Gipe ca. 2012-2014

“Caught visiting his newly-born daughter”, by Lawrence Gipe ca. 2012-2014

A few migrants decline the plea bargain and the judge refers them back to their attorneys. After further conference, most return “willing” to plea. One man with a head injury is sent twice to chat with his lawyer but remains unwilling. The judge tells him to come back another day after he gets medical attention. In other words, be willing to plea.

In an hour and a half, the last defendant has been processed and sent to a private prison. These prisons are profitable. Their lobbyists have successfully convinced lawmakers to increase charges and sentences. What was once no more serious than a traffic ticket is now a felony. Mexicans have been cros

sing the border for years to harvest crops. Many don’t understand the laws have changed. Some are fleeing from starvation or violence in their homeland or only want to rejoin their families.

You’d think a country that put a man on the moon could find a better solution.

Pat Caren is a member of the UU Fellowship of Gainesville, FL, where she volunteers on the Social Justice Committee and is a key coordinator for Family Promise, a program to help homeless and low-income families achieve sustainable independence.