Por La Vida: UUCSJ Delegation Public Statement In Solidarity with the People of Guapinól

Delegation members – Por La Vida 2018

As a human rights delegation to Honduras from November 29 to December 6, 2018 that visited the community of Guapinól in the municipality of Tocoa, Bajo Aguán, we are deeply concerned about the recent police and military occupation occuring there. We have received news as well as photo evidence that police vehicles have blocked the entrance and exit to the community in order to monitor all passage, with participation from the Ministerio Publico. Members of the community are afraid of being unlawfully detained, intimidated, and threatened. The community of Guapinól is defending their water supply from the destruction caused by the nearby mining project of Inversiones Los Pinares, which would destroy their only source of drinkable water.

This occupation comes shortly following the murders of Gerson Leiva and Lucas Bonilla in the nearby community of Ceibita, where community resistance to a mine by the same company, Inversiones Los Pinares, has faced violent repression. There is a documented history of violent acts by state and private business actors against human and land rights defenders in the region of Bajo Aguán.

Our delegation is comprised of clergy members, human rights professionals, educators, and organizers, with the institutional support of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee, UU College of Social Justice, SHARE-EL Salvador, and Leadership Conference of Women Religious.

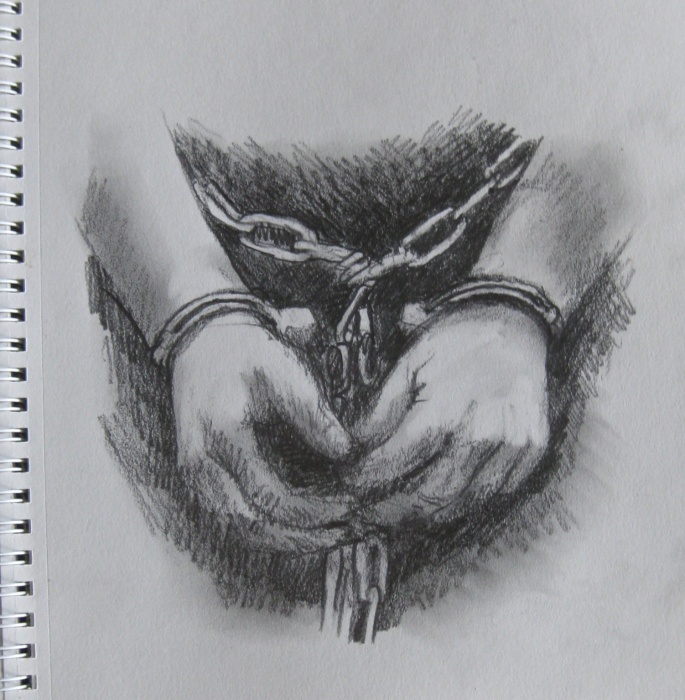

During our delegation we witnessed clear and convincing evidence that there are political prisoners in Honduras, that there is rampant impunity for femicide and the murder of human rights defenders, and that migration and the recent exodus are rooted in systemic violence and loss of livelihoods. The human rights conditions of Honduras do not merit U.S. State Department accreditation, which is currently upheld, a prerequisite for military assistance.

The systemic attack on human rights defenders includes false criminal charges, which we witnessed first-hand at the hearing for Jeremías Martínez, one of at least 18 Guapinól community leaders facing outstanding warrants for their activism.

As people of faith and conscience, we call for:

- An end to police and military occupation of communities in the Bajo Aguán, including Guipinól;

- An immediate investigation into the murders of Gerson Leiva and Lucas Bonillo;

- An end to U.S.military aid and arms sales to Honduras, which have regularly been used by the government of Juan Orlando Hernandez against the country’s own people;

- And the re-introduction and passage of the Berta Caceres Human Rights in Honduras Act in the U.S. Congress.

We continue to follow these cases closely and are in regular communication with leaders from Foro de Mujeres, Mariposas Libres, Mujeres de Aguán, Red de Mujeres Campesinas, and Radio Progreso, ready to respond to new rights violations and conduct ongoing visits. As we continue to support those migrating, we equally support the social movements working to improve conditions that allow for a dignified life and justice for the people of Honduras. We invite all allies to follow the above organizations on social media to increase visibility and support.

Como delegación de derechos humanos que viajó a Honduras entre 29 de Noviembre a 6 de Diciembre 2018, que visitó a la comunidad de Guapinól en la Municipio de Tocoa, Bajo Aguán, estamos profundamente preocupados por la ocupación policial y militar que está pasando allí.

Delegation members around a mandala

Hemos recibido noticias y fotos de patrullas bloqueando la entrada y salida de la comunidad para monitorear todos que vienen y van, con participación del Ministerio Publico. Miembros de la comunidad tienen miedo de ser capturados, intimidados, y amenazados. La comunidad de Guapinól está defendiendo el río de Guapinól de la destrucción que genera la empresa minera operada por Inversiones Los Pinares, la cual destruiría su único acceso al agua potable.

La ocupación sigue el asesinato de Gerson Leiva y Lucas Bonilla en la comunidad de Ceibita, donde han visto represión violento en contra de la resistencia comunitaria a la minería, lo cual pertenece a la misma empresa Inversiones Los Pinares. Hay bastante documentación de los actos violentos por el estado y negocios privados colaborando en contra de los defensores y defensoras de derechos humanos y la tierra en la región de Bajo Aguán.

Nuestra delegación está formado por profesionales religiosos (pastores y una hermana), trabajadores de derechos humanos, educadores, y activistas, con el apoyo institucional de UUSC, UU College of Social Justice, SHARE-El Salvador, y Leadership Conference of Women Religious.

Durante la delegación nosotros fuimos testigos de evidencia clara y persuasivo que hay presos políticos en Honduras, que hay impunidad frecuente por el feminicidio y el asesinato de defensores y defensoras de derechos humanos, y que la migración y el éxodo tienen raíces en violencia sistémica y la pérdida de oportunidades económicas. Los condiciones de los derechos humanos en Honduras no merecen la acreditación del Departamento del Estado de los Estados Unidos, un requisito para ayuda militar.

El ataque sistemática en contra de las defensoras de derechos humanos incluye cargos criminales falsos, lo cual fuimos testigos directamente al corte de Jeremías Martínez, uno de 18 líderes en Guapinól enfrentando órdenes de captura por su activismo.

Como personas de fé y consciencia, demandamos:

- La parada de ocupación policial y militar en las comunidades de Bajo Aguán, incluso Guapinól;

- Una investigación inmediata de los asesinatos de Gerson Leiva y Lucas Bonillo;

- La parada de ayuda militar y venta de armas de los Estados Unidos a Honduras, que estan usados en contra de la gente por el gobierno de Juan Orlando Hernandez;

- Y el pasaje de la Acta Berta Cacares para Derechos Humanos en Honduras en el Congreso de los Estados Unidos.

Seguimos vigilando lo que está pasando en Guapinól y en estos casos. Estamos en comunicación con las líderes de Foro de Mujeres, Mariposas Libres, Mujeres de Aguán, Red de Mujeres Campesinas, y Radio Progreso, y estamos pendientes para condemnar nuevos violaciones. Como seguimos solidarizandonos con los migrantes, igual nos solidarizamos con los movimientos sociales de Honduras que están luchando para mejorar los condiciones para una vida digna y justicia en Honduras. Invitamos a todos aliados que siguen las páginas de facebook y los redes sociales de estas organizaciones para seguir aumentando su visibilidad.

The Via Crucis we followed last month in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, was different. It demonstrated vividly the power and peril faced by those whose deepest faith compels them to stand up against oppression. The cross they carried was covered with words — poverty, violence, hatred, murders, torture, imprisonment – naming explicitly the weight the people carry, under the repressive presidency of Juan Orlando Hernandez. Those in the procession also carried 34 smaller crosses, each one bearing the name of a person who had been shot and killed by security forces in the past two months, since the fraudulent election that ensures Hernandez will continue in power.

The Via Crucis we followed last month in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, was different. It demonstrated vividly the power and peril faced by those whose deepest faith compels them to stand up against oppression. The cross they carried was covered with words — poverty, violence, hatred, murders, torture, imprisonment – naming explicitly the weight the people carry, under the repressive presidency of Juan Orlando Hernandez. Those in the procession also carried 34 smaller crosses, each one bearing the name of a person who had been shot and killed by security forces in the past two months, since the fraudulent election that ensures Hernandez will continue in power.