by Heather Vickery | May 13, 2016 | Congregational Trip, Immigration

Kim Duncan is a CSJ program leader from Portland Oregon. She led a delegation from two churches in Oregon, including her own.

Last October, a group from three UU congregations in Oregon went on CSJ’s Border Justice tour on the Arizona – Mexico border. On April 19th, we presented our experiences following the service at the First Unitarian Church of Portland. It was a rousing success!

Homemade Mexican tamales made by our friend, whose husband many of us have supported while he was in sanctuary in Portland – as well as an interest in US immigration policy and border conditions – drew nearly 40 people at Portland’s First Unitarian Church on Sunday.

What they heard, and what we were privileged to report on, were the experiences both wrenching and uplifting, that confronted us during our six day journey with CSJ partner, BorderLinks, in Tucson, Arizona.

We confronted a wall that was ugly, high and forbidding along our border. We saw altars along the desert migrant trails, commemorating the deaths of those who tried to cross but failed. We met migrants in Mexico who said they would continue to cross, in spite of the risks, because the danger they fled in Central America is worse, or because there are jobs waiting for them in the US. We saw the cast-off belongings left behind in the desert as immigrants made their way north. We witnessed 50 shackled migrants appear together in a courtroom and within a half-hour be mustered out and deported back to the border or to jail. We learned that private prison companies are making profits out of our border policies.

We were appalled.

We didn’t get clear answers about how to remedy this mess, but we met many heroic individuals trying to relieve the day-to-day suffering and angst in their communities. We met with people and organizations providing hidden way-stations in the desert that supply water and medical care to migrants; we talked with advocates trying to change the court processing; we visited with a woman named Rosa who was in sanctuary for over a year in Tucson, whose faith was inspiring. We were relieved to hear that her faith was rewarded a month later when she was free to go home.

We were humbled and touched by these experiences.

We presented this and more on the 19th. We replicated the cross planting ceremony that we performed with Frontera de Cristo in Douglas – honoring those who gave their lives for a better life. We invited speakers knowledgeable on US border policy and the violence that is pushing people to leave their homes and risk everything to come to the US.

We presented this and more on the 19th. We replicated the cross planting ceremony that we performed with Frontera de Cristo in Douglas – honoring those who gave their lives for a better life. We invited speakers knowledgeable on US border policy and the violence that is pushing people to leave their homes and risk everything to come to the US.

Today, many in our group are at work in Portland helping where we can with individuals and families affected by our country’s immigration policies. We are advocating for Congressional action to fix this nightmare and we are endorsing efforts to divest funds in organizations invested in private prisons.

There aren’t any simple answers, we know that. But we saw our nation’s current policies in action – which waste lives, build terrible resentments, and punish desperate people who, like some of our own forebearers, are seeking better futures.

We can do so much better for them and for us.

by Heather Vickery | Jan 29, 2016 | Congregational Trip, Immigration

Tucson, Arizona – November 2015

“Sentencing” by Lawrence Gipe, ca. 2012-2014

Sixty two detainees, migrants from Mexico and Central America caught crossing the border illegally, sit in the large courtroom facing the judge. On his right is an interpreter. Our BorderLinks contingent sits in back to witness the proceedings, to keep the system “honest.”

The judge asks the group, “Do you understand why you are here?” “Do you understand the charges against you?” “Have you had an opportunity to talk with your attorney?” The defendants are instructed to stand if they don’t comprehend. No one stands.

The judge calls out names, stumbling over pronunciations. Five men, one woman, and their lawyers stand before him. Each is charged with a felony and has the option to plea to a misdemeanor and waive trial. One by one, the judge recites a litany to this effect. One by one, they plead guilty to the misdemeanor, waiving their right to trial, and are given sentences of up to 180 days.

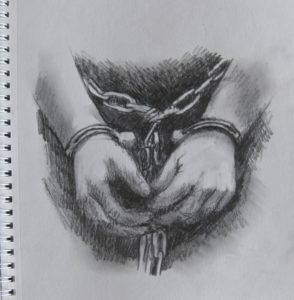

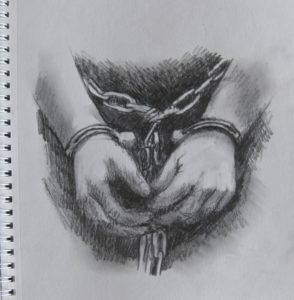

“Shackled” by Lawrence Gipe ca. 2012-2014

I’m struck by the politeness between the judge and the accused. Many answer his questions, “Si, senior.” The judge always finishes with, “Thank you for your time, and good luc.” The convicted often reply, “Gracias.”

Six human beings processed in less than ten minutes: First Appearance, Arraignment, Plea Bargaining, Sentencing. Very streamlined, very efficient. Is this American justice?

The convicted pass by us as they’re taken from the courtroom, looking resigned. Do they see empathy in our faces? Or only a sea of white faces, curious and judgmental?

All are handcuffed and shackled. What threat do these Mexican peasants pose? They’re accused of illegal border crossings, not dangerous crimes. All wear clothes they were arrested in, some cleaner than others, depending on how long they’d been in the desert and in jail.

The scene repeats itself. One man on crutches, legs shackled, is handcuffed to his crutches. Did he walked through the desert on crutches? Stories abound of Border Patrol officers abusing migrants, sometimes getting away with murder. Other stories tell of Border Patrol humanitarians who save lives.

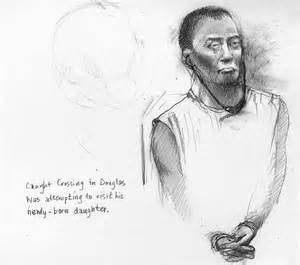

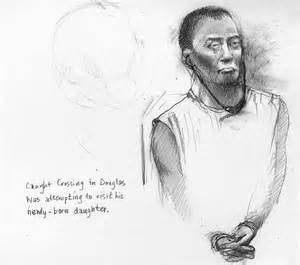

“Caught visiting his newly-born daughter”, by Lawrence Gipe ca. 2012-2014

A few migrants decline the plea bargain and the judge refers them back to their attorneys. After further conference, most return “willing” to plea. One man with a head injury is sent twice to chat with his lawyer but remains unwilling. The judge tells him to come back another day after he gets medical attention. In other words, be willing to plea.

In an hour and a half, the last defendant has been processed and sent to a private prison. These prisons are profitable. Their lobbyists have successfully convinced lawmakers to increase charges and sentences. What was once no more serious than a traffic ticket is now a felony. Mexicans have been cros

sing the border for years to harvest crops. Many don’t understand the laws have changed. Some are fleeing from starvation or violence in their homeland or only want to rejoin their families.

You’d think a country that put a man on the moon could find a better solution.

Pat Caren is a member of the UU Fellowship of Gainesville, FL, where she volunteers on the Social Justice Committee and is a key coordinator for Family Promise, a program to help homeless and low-income families achieve sustainable independence.

by Heather Vickery | Dec 8, 2015 | Congregational Trip, Immigration

This post was written by Pat Caren from the UU Fellowship of Marion County Borderlinks trip in November 2015.

To cross a desert on foot is to risk your life. In Cochise County, Arizona, more than 260 people have perished this way since 2009. Every Tuesday evening in the border town of Douglas, the Healing Our Borders Prayer Vigil is held in remembrance of those and thousands of others who have died. In November, I participated in this moving experience, one of a delegation of fifteen from the Unitarian Universalist College of Social Justice.

Presbyterian minister Mark Adams led the vigil. Other participants included a group of Presbyterian Youth and other human rights workers and concerned individuals. We loaded 260 or so white wooden crosses into a shopping cart. Each took three and we lined up along the street that leads to the Mexican border. Most crosses bore a name and dates of birth and death.

Beginning with Pastor Mark, each held up a cross and spoke the name on it. Everyone else said, “Presente!” Then the cross was laid against the curb and its holder moved to the end of the line. Down the street we progressed. When my turn came, I did my best to pronounce the name. Everyone echoed, “Presente!” As we set down our last cross, we took another from the cart and continued, announcing names, “Presente,” laying them down.

One of mine had no name, only “Mujer no identificada.” Who was she? Certainly someone’s daughter, probably someone’s sister. If married, where was her husband? Represented by another cross? Or did he survive to go on, unable to report her death or claim her body? Did she have children? Were they waiting for her to join them in the US or did she leave them behind to find work so she could feed them?

And why, oh why, do we not know her name? Were her remains so scattered that no clothing, papers, or possessions could be traced to her?

After the last cross, save three, had been laid down, we gathered in a circle. One by one, Pastor Mark announced two more names and another unknown, “Presente!” and he laid each cross in the center of our circle.

Standing in the night, listening to prayers for the families of the fallen and for both of our countries, remembering the dead and praying for a peaceful solution, I was struck by the tragedy of so many hopeful lives cut short.

Whatever you may think of those who were lost, about their motivations, their judgment—they were living, breathing souls, like you and me, with hopes and dreams, struggles and sorrows. Some died alone, some in the company of friends or loved ones. And even the unknowns, the No identificada, were loved and mourned by someone.

We returned to the parking lot, picking up the crosses as we went, mourning for our brothers and sisters, those children of God, whom we never met on this side of the border between life and death, but who had become real to our hearts.

Pat Caren is a member of the UU Fellowship of Gainesville, FL, where she volunteers on the Social Justice Committee and is a key coordinator for Family Promise, a program to help homeless and low-income families achieve sustainable independence.

by Deva Jones | Nov 13, 2015 | Congregational Trip

We were shocked, we were saddened, and we are compelled to tell others about the violation of human rights perpetrated by our government. The economic and political systems of the global north have systematically undermined the livelihoods and survival of the most vulnerable of our neighbors to the south.

We were shocked, we were saddened, and we are compelled to tell others about the violation of human rights perpetrated by our government. The economic and political systems of the global north have systematically undermined the livelihoods and survival of the most vulnerable of our neighbors to the south.

We were members of a human rights delegation to the border with Mexico last month through the Unitarian Universalist College of Social Justice coordinated with Tucson-based BorderLinks.

Our delegation of eleven was led through five days of exposure to the unique and harrowing culture of the U.S./Mexican borderlands.

Several of us in the UUSC local action group have supported Francisco Aguirre and his family who spent three months in sanctuary at Augustana Lutheran Church in Portland last fall. We also participate in the activities of the Interfaith Movement for Immigrant Justice.

Through the delegation experience, we learned the impact and role of labor history and policies such as NAFTA, on the plight of many Mexican and Central American communities. At the border we saw firsthand the incredible militarization of that strip of land. There was the imposing wall, the six hundred border patrol staff in the Tucson sector, the vehicles, the drones, the lights, the cameras, and the sensors. We are apparently at war.

We learned though our conversations with Frontera de Cristo and No More Deaths that the people crossing the border are classified as criminals. Through the use of checkpoints even the desert is used as a “lethal” deterrent. The very landscape is a weapon.

Our government has criminalized migrants. We witnessed this as our group attended “Operation Streamline” in the Tucson Federal Courthouse where we observed 55 shackled individuals take plea bargains and be sentenced between 30 and 180 days apiece to private corporate-run prisons before being deported. These private corporations contract with our government who simultaneously pays for the border patrol agents who assure that there are people to imprison.

We witnessed some amazing resistance to the dehumanization of the border. We went to an organization in Agua Prieta where women who were formerly involved in the miserable maquiladora factories are growing permaculture gardens, learning to feed their children healthy foods, and gaining leadership skills. We met Shura Wallin, a retired Californian who goes out into the desert with the Green Valley Samaritans to provide water and support to the men, women and children who daily cross over into the harsh Sonoran desert. In Arivaca we heard about the desert clinic and support systems coordinated by No More Deaths. And in Tucson we met Rosa and her supporters at Southside Presbyterian who has persevered in sanctuary there for over fifteen months.

You can become involved. Take action. Join the UUSC Action Group; attend an Interfaith Movement for Immigrant Justice (IMIrJ) meeting and find ways to support our immigrant sisters and brothers. Learn more about our trip to the borderlands; see photos of our experience by visiting our church website. Come for a presentation by one the humanitarian aid workers of No More Deaths on November 30, 6:30 PM at First Unitarian.

by Deva Jones | Jun 19, 2015 | Congregational Trip, Immigration

This post was written by Reyna Grande, a participant of the 2015 May Border Justice journey with UUCSJ.

Thirty years ago last month, I crossed the border illegally through Tijuana. At nine years old, I found myself running through the darkness, trying to find a place to hide from the ever-watching eyes of “la migra”. I crossed the border for one reason—to be reunited with my father, whom I hadn’t seen in eight years. I was lucky. I made it on my third attempt, and I began my new life in the U.S. with my father by my side. I went on to become the first in my family to graduate from college. I went on to become an award-winning writer published by Simon & Schuster.

But I never forgot where I came from.

This is why thirty years after my crossing, I decided to go back to the border and experience it through the eyes of an adult. I joined the UU College of Social Justice border delegation and headed to Tucson, Arizona where I met with the others in the group: Jose, Debbie, Marguerite, Briana, Roberta, Ian, and our guide, Emrys.

Early the next day we headed to Douglas, Arizona. The first thing on the agenda was to see the border wall. I’d seen pictures of it, but those pictures didn’t quite prepare me for the experience of actually being there, standing before this huge monstrosity as I pondered on what it represented, on the effect it has had on the people living on either side of it. As the group stood by the wall, we could feel the wind howling through the slats, forcing its way through the wall. Emrys said, “Look, even the wind has a hard time getting through.” Yes, this wall was meant to keep people out, but even the wind had to struggle on its own journey north.

After the border wall, we went to Agua Prieta to visit a women’s co-op and then a co-op of coffee growers called Café Justo. In the evening, we went to a migrant shelter to have dinner with the migrants. This was for me, the part that touched me the most. I had never set foot on a migrant shelter before. As I sat there, eating a dinner of beans, rice, and squash, I looked at the migrants around me. They told us their story, and as we listened I looked at those men’s faces and I thought about my father. He’d been the first migrant in our family. He’d headed north when I was only two years old to pursue a better life for his family. As I looked at those men I couldn’t help but wonder about the families they had left behind, and how much responsibility these migrants carried on their shoulders. Whatever happened to them—there in the border—would seal not just their own fates, but their families’ as well.

The next day, we returned to Agua Prieta to visit the Migrant Resource Center. It was not opened when we arrived, so we waited outside the door. There were a few migrants waiting as well, and I took the opportunity to go talk to one of them. He told me his border crossing had not gone well and he’d decided to return to his home, but he had no money for the bus fare and was hoping the Center would be able to help him. I asked him questions about his home, and he told me about the poverty, the low wages that had driven him north. He said, “I’ve failed, but now when I go home at least I won’t be fantasizing about the U.S. anymore. Now I know the hard reality—that I’m stuck in Mexico, that there’s nowhere to go.”

It saddened me to think of this man returning to his home with broken dreams. It infuriated me because I knew first-hand the poverty he was trying to escape from, and I wished he’d succeeded. Then I felt guilty, too, because I had “made” it. And he hadn’t.

On the second-to-the last day, we teamed up with the organization No More Deaths to do a water drop-off. We carried 16 water jugs and bags up food up a 1.5 mile hike. As we struggled through the bushes, our feet getting covered in dust, I thought about my border crossing. I remembered hiding in the bushes while a helicopter flew above us. I remembered wishing I were invisible. We left the water and food by a dry creek. As we made our way back, I kept thinking about the migrants who walked on that trail. I scanned the bushes and wondered how many of them were out there now. I hoped that when they found the food and water we’d left, their faith would be renewed and they’d find the strength to continue on their journey.

One of the last conversations we had as a group was what steps we would all take to continue our mission to educate people about the border and to help the migrant population. Everyone had different ideas, and I was happy to see that every single one of us was deeply committed to making a difference. I had recently run two successful fundraisers, so upon my return to Los Angeles I launched a fundraiser on behalf of Casa del Migrante. In nine days, I’ve raised over $1,000. There’s still a month left to go and by the end of it, I’ll pay a visit to Casa del Migrante. One thing I learned from the border delegation is that we all have it in our power to do SOMETHING, no matter how small or how little, to help migrants in their journeys: From talking about migrants as human beings instead of statistics, donating to organizations that help migrants, putting pressure on our government to treat migrants with compassion and dignity, to participating in border delegations.

So what will you do today?

by Deva Jones | Aug 14, 2014 | Congregational Trip, Racial Justice

The following reflection was written by Gordon Gibson, a civil rights leader and organizer.

This was originally posted in The Memphis Commercial Appeal here.

Why would people from around the country go to Mississippi, especially in the heat of July?

50 years ago hundreds of people went to Mississippi in June, July, and August to make a difference by joining with local residents to confront the state’s long history of racial discrimination.

This past July, I co-led a small group that went to Mississippi to encounter the history that was made 50 years ago. This is American history, important American history. Unlike the Shiloh Battlefield or Boston’s Freedom Trail, this is history where you can still meet and talk with some of the history-makers and learn about the history involving deep ethical issues of justice and human rights.

For people of religious sensibility, human rights and elemental justice were important in 1964’s “Freedom Summer,” and those values remain important today. The Living Legacy Project and the Unitarian Universalist College of Social Justice, co-sponsors of our trip, have been organizing such pilgrimages to introduce people to the sites and veterans of the civil rights movement because both organizations have found that these encounters can transform people from being “concerned for human rights” to being workers for human rights.

Those of us on the bus included a range of ages from teens to seventies, a range of knowledge from virtually none to some civil rights participation, and current residence all across the United States. What were some of the people, places, and issues that we encountered?

We heard from people deeply involved in leadership of the Mississippi Summer Project (the actual name of “Freedom Summer”), that there was disagreement then that continues now over bringing in hundreds of volunteers, most of them white college students. Did this disempower local residents who had been working for several years with the three or four dozen full-time civil rights workers in Mississippi? Or did it affirm the local residents by letting them know that they were not alone and isolated? Did the influx of volunteers put local people at greater risk of harassment by making their civil rights activities more obvious, or did it provide them a measure of protection by making any harassment an issue far beyond Mississippi?

We talked with grassroots volunteers like Roscoe Jones. In 1964, Roscoe Jones was 17 years old and had been assigned by Mickey Schwerner to lead the Freedom School in Meridian. Freedom Schools, one of the three main programs of the Summer Project, taught everything from basic literacy and black history to subjects like French. Roscoe Jones told us that, with 300 children and adults, Meridian’s was the largest Freedom School in the state. He spoke clearly to his goal in Freedom Summer (and in his work since): “equality,” and he noted that equality might or might not include integration.

We met the very impressive family of Vernon Dahmer, Sr. They continue to live on family-owned land north of Hattiesburg, and Mrs. Dahmer lives in the house re-built on the site where Mr. Dahmer was fatally injured in a 1966 arson attack by the Klan. Vernon Dahmer, Sr. was a long-time leader in getting members of the local black community registered to vote. The Klan executed him for advocating this bedrock American right, and three of his sons had to come home from military service to bury their father.

The Dahmer family has continued its service to the community (helping to restore an historic Rosenwald School, for example), and has welcomed successful prosecution of the Klan attackers. But it has also forgiven those involved in the attack who have admitted what they did and sought reconciliation.

The list of people and places we encountered in one week could go on: standing in Medgar Evers’ living room, seeing the crumbling remains of the store in Money where 14 year-old Emmett Till ran afoul of “the southern way of life,” honoring the persons and the burial places of James Chaney and Fannie Lou Hamer, listening to the personal accounts of the Rev. Ed King and Hollis Watkins, hearing people tell of the Klan beating of family members at the Mount Zion United Methodist Church near Philadelphia before the church building was burned…

I hope and believe that members of our group learned in their visit to Mississippi that a small group of dedicated people working in harmony with the best of American and religious principles can bring change. And I look forward to hearing from them over coming years of their own work as change agents.

We presented this and more on the 19th. We replicated the cross planting ceremony that we performed with Frontera de Cristo in Douglas – honoring those who gave their lives for a better life. We invited speakers knowledgeable on US border policy and the violence that is pushing people to leave their homes and risk everything to come to the US.

We presented this and more on the 19th. We replicated the cross planting ceremony that we performed with Frontera de Cristo in Douglas – honoring those who gave their lives for a better life. We invited speakers knowledgeable on US border policy and the violence that is pushing people to leave their homes and risk everything to come to the US.