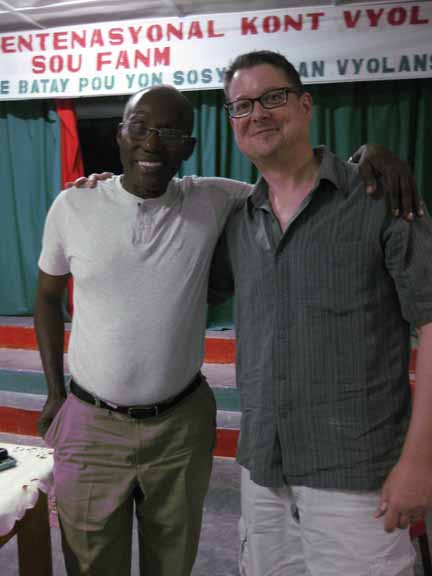

Jon McGoran (right) with MPP Director, Chavannes Jean-Baptiste.

This post was written by Jon McGoran, a participant on the 2015 Main Line delegation to Haiti.

Halfway through our one-week visit to Haiti with the Unitarian Universalist College of Social Justice (UUCSJ) and Mouvement Payizan Papay (MPP), I’ve already encountered so many compelling images, people, and experiences that I’ll be processing them for months, and remembering them for a lifetime. Much of the visit has been marked by stark contrasts: The grinding poverty and the natural beauty. The isolation of being a stranger in a strange land and the warmth and friendliness of the people we have met. Even the animal life we have encountered — on our first morning working at the MPP center, we stumbled upon a tarantula and a seven-inch centipede (which gave some in our group quite a shock) and then found that one of the goats had given birth the night before. Among other things I’ve learned here: little baby goats are incredibly cute.

Other contrasts were not so obvious, but may be more compelling. Haiti is a land with many problems and not an abundance of resources to fix them. In the weeks leading up to this trip, there was plenty of reading and discussion about Haiti and its history. (Part of the reason I came here was for a book I am working on, so I had already been doing plenty of research.) These past few months have been eye-opening, learning of Haiti’s history and the many injustices that have been inflicted on it from without — and sometimes from within.

One word common to many of these accounts is ‘hopeless,’ and in just a few days I’ve seen much that would explain why some would say that. But I’ve also seen that hope is something that Haiti has in abundance.

The 2010 earthquake was a tragedy of a magnitude that could easily have erased all hope. Five years later, traveling through Port au Prince, plenty of damage is still visible, still unrepaired. But traveling with others who have been here several times since then, it is incredibly heartening to witness their observations, second hand, about which buildings and infrastructure have been repaired or rebuilt, which improvements are new since a year ago or two. There is much work still to do, but clearly, progress has been made.

Less visible but more devastating than Haiti’s physical damage was the damage to its people — those who perished or were injured, and those who survived and were left to deal with the trauma and destruction.

But with MPP, there is hope for these survivors as well. MPP is helping Haitians build healthy and fulfilling lives through sustainable small-scale agriculture, through training and education and material support, and also by building a series of eco-villages, where Haitians displaced by the 2010 earthquake can live those fulfilling lives, away from the terrible conditions of Port au Prince.

MPP is cause for inspiration in and of itself. Since its founding with a handful of members over forty years ago by Chavannes Jean-Baptiste, the organization has grown to 60,000 members. The eco-villages are even more cause for hope. At the recently-built school that serves all six villages, we had a joyous visit with the students and parents. An impromptu musical exchange broke out, with members of our delegation and small groups of school children trading off performances of some favorite songs. We also visited several of the villages, including village four, which was already boasting mature trees and robust individual and communal agricultural operations. Perhaps the most moving moment for me was when we visited village six, the newest one, only four or five months old. Before we made natural insecticide together, pounding garlic and neem leaves, and grating sour orange peel and onions, the villagers each introduced themselves. The last to do so was a man who quietly explained that he had been in the village for one month. He was from Port au Prince. He had lost his wife and his two daughters in the earthquake, and since that time he’d been homeless and foraging for food. I was stunned, unable to imagine what his life had been like and how he had managed to continue it. I felt an overwhelming sense of sorrow and tragedy, of hopelessness. But in his eyes I saw hope. After a pause, he added, “Thanks to Chavannes and MPP, now I have a home.”

Bio: JON McGORAN has been writing about food and sustainability for over twenty years, as communication director at Weavers Way Co-op and as editor in chief at Grid magazine. He is also the author of the ecological thrillers Drift and Deadout, as well as their forthcoming sequel, which will be set in part in Haiti.