by Deva Jones | Nov 13, 2015 | Congregational Trip

We were shocked, we were saddened, and we are compelled to tell others about the violation of human rights perpetrated by our government. The economic and political systems of the global north have systematically undermined the livelihoods and survival of the most vulnerable of our neighbors to the south.

We were shocked, we were saddened, and we are compelled to tell others about the violation of human rights perpetrated by our government. The economic and political systems of the global north have systematically undermined the livelihoods and survival of the most vulnerable of our neighbors to the south.

We were members of a human rights delegation to the border with Mexico last month through the Unitarian Universalist College of Social Justice coordinated with Tucson-based BorderLinks.

Our delegation of eleven was led through five days of exposure to the unique and harrowing culture of the U.S./Mexican borderlands.

Several of us in the UUSC local action group have supported Francisco Aguirre and his family who spent three months in sanctuary at Augustana Lutheran Church in Portland last fall. We also participate in the activities of the Interfaith Movement for Immigrant Justice.

Through the delegation experience, we learned the impact and role of labor history and policies such as NAFTA, on the plight of many Mexican and Central American communities. At the border we saw firsthand the incredible militarization of that strip of land. There was the imposing wall, the six hundred border patrol staff in the Tucson sector, the vehicles, the drones, the lights, the cameras, and the sensors. We are apparently at war.

We learned though our conversations with Frontera de Cristo and No More Deaths that the people crossing the border are classified as criminals. Through the use of checkpoints even the desert is used as a “lethal” deterrent. The very landscape is a weapon.

Our government has criminalized migrants. We witnessed this as our group attended “Operation Streamline” in the Tucson Federal Courthouse where we observed 55 shackled individuals take plea bargains and be sentenced between 30 and 180 days apiece to private corporate-run prisons before being deported. These private corporations contract with our government who simultaneously pays for the border patrol agents who assure that there are people to imprison.

We witnessed some amazing resistance to the dehumanization of the border. We went to an organization in Agua Prieta where women who were formerly involved in the miserable maquiladora factories are growing permaculture gardens, learning to feed their children healthy foods, and gaining leadership skills. We met Shura Wallin, a retired Californian who goes out into the desert with the Green Valley Samaritans to provide water and support to the men, women and children who daily cross over into the harsh Sonoran desert. In Arivaca we heard about the desert clinic and support systems coordinated by No More Deaths. And in Tucson we met Rosa and her supporters at Southside Presbyterian who has persevered in sanctuary there for over fifteen months.

You can become involved. Take action. Join the UUSC Action Group; attend an Interfaith Movement for Immigrant Justice (IMIrJ) meeting and find ways to support our immigrant sisters and brothers. Learn more about our trip to the borderlands; see photos of our experience by visiting our church website. Come for a presentation by one the humanitarian aid workers of No More Deaths on November 30, 6:30 PM at First Unitarian.

by Deva Jones | Jun 19, 2015 | Congregational Trip, Immigration

This post was written by Reyna Grande, a participant of the 2015 May Border Justice journey with UUCSJ.

Thirty years ago last month, I crossed the border illegally through Tijuana. At nine years old, I found myself running through the darkness, trying to find a place to hide from the ever-watching eyes of “la migra”. I crossed the border for one reason—to be reunited with my father, whom I hadn’t seen in eight years. I was lucky. I made it on my third attempt, and I began my new life in the U.S. with my father by my side. I went on to become the first in my family to graduate from college. I went on to become an award-winning writer published by Simon & Schuster.

But I never forgot where I came from.

This is why thirty years after my crossing, I decided to go back to the border and experience it through the eyes of an adult. I joined the UU College of Social Justice border delegation and headed to Tucson, Arizona where I met with the others in the group: Jose, Debbie, Marguerite, Briana, Roberta, Ian, and our guide, Emrys.

Early the next day we headed to Douglas, Arizona. The first thing on the agenda was to see the border wall. I’d seen pictures of it, but those pictures didn’t quite prepare me for the experience of actually being there, standing before this huge monstrosity as I pondered on what it represented, on the effect it has had on the people living on either side of it. As the group stood by the wall, we could feel the wind howling through the slats, forcing its way through the wall. Emrys said, “Look, even the wind has a hard time getting through.” Yes, this wall was meant to keep people out, but even the wind had to struggle on its own journey north.

After the border wall, we went to Agua Prieta to visit a women’s co-op and then a co-op of coffee growers called Café Justo. In the evening, we went to a migrant shelter to have dinner with the migrants. This was for me, the part that touched me the most. I had never set foot on a migrant shelter before. As I sat there, eating a dinner of beans, rice, and squash, I looked at the migrants around me. They told us their story, and as we listened I looked at those men’s faces and I thought about my father. He’d been the first migrant in our family. He’d headed north when I was only two years old to pursue a better life for his family. As I looked at those men I couldn’t help but wonder about the families they had left behind, and how much responsibility these migrants carried on their shoulders. Whatever happened to them—there in the border—would seal not just their own fates, but their families’ as well.

The next day, we returned to Agua Prieta to visit the Migrant Resource Center. It was not opened when we arrived, so we waited outside the door. There were a few migrants waiting as well, and I took the opportunity to go talk to one of them. He told me his border crossing had not gone well and he’d decided to return to his home, but he had no money for the bus fare and was hoping the Center would be able to help him. I asked him questions about his home, and he told me about the poverty, the low wages that had driven him north. He said, “I’ve failed, but now when I go home at least I won’t be fantasizing about the U.S. anymore. Now I know the hard reality—that I’m stuck in Mexico, that there’s nowhere to go.”

It saddened me to think of this man returning to his home with broken dreams. It infuriated me because I knew first-hand the poverty he was trying to escape from, and I wished he’d succeeded. Then I felt guilty, too, because I had “made” it. And he hadn’t.

On the second-to-the last day, we teamed up with the organization No More Deaths to do a water drop-off. We carried 16 water jugs and bags up food up a 1.5 mile hike. As we struggled through the bushes, our feet getting covered in dust, I thought about my border crossing. I remembered hiding in the bushes while a helicopter flew above us. I remembered wishing I were invisible. We left the water and food by a dry creek. As we made our way back, I kept thinking about the migrants who walked on that trail. I scanned the bushes and wondered how many of them were out there now. I hoped that when they found the food and water we’d left, their faith would be renewed and they’d find the strength to continue on their journey.

One of the last conversations we had as a group was what steps we would all take to continue our mission to educate people about the border and to help the migrant population. Everyone had different ideas, and I was happy to see that every single one of us was deeply committed to making a difference. I had recently run two successful fundraisers, so upon my return to Los Angeles I launched a fundraiser on behalf of Casa del Migrante. In nine days, I’ve raised over $1,000. There’s still a month left to go and by the end of it, I’ll pay a visit to Casa del Migrante. One thing I learned from the border delegation is that we all have it in our power to do SOMETHING, no matter how small or how little, to help migrants in their journeys: From talking about migrants as human beings instead of statistics, donating to organizations that help migrants, putting pressure on our government to treat migrants with compassion and dignity, to participating in border delegations.

So what will you do today?

by Deva Jones | Aug 1, 2014 | Immigration

The following statement was written by Rev. Kathleen McTigue, Director at the UU College of Social Justice (UUCSJ), on July 31, 2014 following her arrest during a protest at the White House.

We’re gathered together here as people of faith, as well as conviction. We come from many different faiths, so I wouldn’t presume to know all the reasons so many of you have gathered. But I can tell you why the Unitarian Universalists are here.

We’re among those who find our home on the religious spectrum at the place that is most thoroughly grounded in this world, in this one precious and fleeting life. We are the religious descendants of people who believed that the God they knew, the God of pure love, could want only good things for every human being.

So these ancestors of ours rejected the idea that God has a hell waiting for us after death. Instead, they pointed to all of the ways we human beings create hell for each other, right here on earth. Their faith called them to do something about that very real and present hell. Our faith — the same faith — is calling out to us still.

That’s why we are here, as Unitarian Universalists. We see the hell of hopelessness that’s been created for immigrants who are lost in detention, the hell of anguish when family members are torn away from each other, the hell of fear when people are so scared of deportation that they can’t call the police when they need them. We see the suffering and the deaths caused by turning our borders into military zones. And we see the desperation that drives tens of thousands of children to flee their homes with nothing but a little sliver of hope that they might find safety here.

Religion, at its core, is not about our beliefs. Real religion is about what we do with our beliefs. Our faith calls us to act, in every way we can, to ease the suffering of migrants and to demand justice in our immigration laws. So today we call on President Obama — our elected leader — to lead us now in the right direction, and to join us in standing on the side of love. May it be so.

by Deva Jones | Apr 16, 2014 | Congregational Trip, Immigration

The following post was written by Rev. Kathleen McTigue, Director at the UU College of Social Justice (UUCSJ).

The long morning walk in the desert that stretches along the Arizona-Mexico border was eye-opening and heartbreaking. I was there a few weeks ago with a group of seminary students on our program with BorderLinks called “Theology and Migration.” We hoped to better understand the reality of these borderlands between countries and the many entwined justice issues that lead so many people to literally risk their lives — in the simple, essential search for work.

We walked through a stunningly beautiful landscape, filled with spring birdsong and blossoms, the horizon formed by sharp desert mountains. But the sun, harsh terrain, and lack of water made it a profoundly dangerous place to walk, even in broad daylight with sturdy shoes. We were warned to watch out for the cholla cactuses and even so, several of us got them caught in our shoes and clothing; they pierce easily and are very painful. The migrants who try to cross this desert do it at night, in cheap shoes that can fall apart in a matter of hours. For them, stepping on a cholla — or having the soles come off their shoes — can mean the end of their lives.

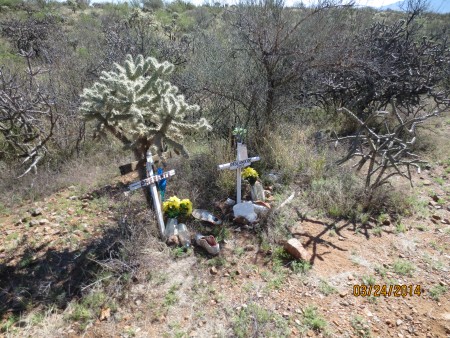

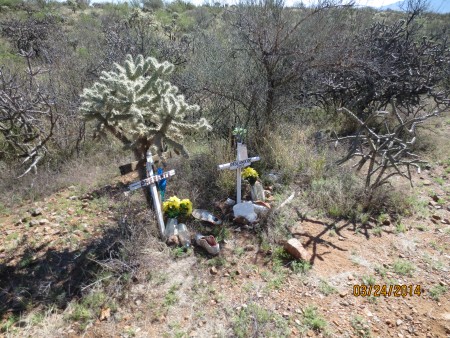

We learned that in this area over the past ten years, the remains of over 3,000 people have been found. Three thousand human beings in ten years! And the desert is a big place: those are just the bodies that have been found. Volunteers with groups like Samaritans and No More Deaths mark the places where people have died with simple white crosses of wood or pipe, with the word desconocido — “unknown person” — and the year they were found. In an effort to keep others from dying, they go out along these migrant trails every day, carrying gallons of water and the willingness to bring those they find into town to a hospital — an act that risks a felony charge under current law.

We spent a full week in Arizona and Mexico, hearing stories from migrants, clergy, volunteers of many stripes, and immigration officials. We sat in on court hearings as migrants in shackles were sentenced to many months in prison because they were caught for a second or third time crossing the border. We prayed at the border wall, a towering steel structure surrounded by stadium lights, mounted cameras, and armed guards. We saw first hand the degree to which an issue of civil law has been thoroughly militarized: our borders are like a war zone.

Now I am back home in Boston, more determined than ever to add my own voice to the demand for immigration reform. I urge you to consider joining us in the coming year on one of these journeys to the border, or contact us about scheduling a group from your congregation for this program. You will be moved, inspired and empowered — because no matter where we live, immigration justice calls us to action.

by Deva Jones | Feb 19, 2013 | Immigration

The following post was written by Rev. Lisa Bovee-Kemper, assistant minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Asheville, N.C. She recently took part in the February 2013 BorderLinks: Immigration Justice Tour with the UU College of Social Justice.

Today is day three of our delegation. Our group hails from as close as Phoenix, Ariz., and as far as Massachusetts. In some sense it feels like the trip is going so quickly, and in other ways it feels like we have been together for a long time. It is a paradoxical journey, one that brings us into deeper connection with one another and with our own spiritual path at the same time that it shines a bright and unforgiving light on the harsh realities of life in the borderlands.

We began our journey in Nogales, Mexico, where we spent the night at Hogar de Esperanza y Paz (Home of Hope and Peace, or HEPAC), a community center that provides education and support to children and adults living in Nogales. The philosophy at HEPAC is that there is no time to wait for the government to change the laws — the people must create their own hope and justice here and now in Mexico, to make life better for the people today. We also visited Grupos Beta, a government-run agency that assists migrants who have recently been sent back from the United States. The people we met there were profoundly inspiring as they shared their stories. Though they had been through unimaginable difficulty and had been separated from their families, they remained hopeful and determined to make a better life for themselves and their families one way or another.

In addition, we have walked one of the migrants’ paths in the desert with a humanitarian aid volunteer and heard a presentation from Mike Wilson, who is a member of the Tohono O’odnam nation and leaves water in the desert on tribal lands, defying the orders of the tribal council. Tomorrow we will visit Immigration and Customs Enforcement and meet with a public defender.

Our experiences so far have been at turns heartbreaking and shocking, inspiring and hopeful. We have seen the ways that U.S. policies and the militarization of the border create a humanitarian crisis beyond what I could have imagined. There are “death maps,” which show red dots where human remains have been found, and there are places where there are so many dots on top of one another that you can’t see where one ends and the others begin. We have seen some of the things that have been left behind in the desert — prize possessions dropped in a moment of desperation, photos of dog bites and feet blistered beyond recognition. And we have heard stories of the triumph of kindness and compassion, even in the midst of these tragedies.

I find myself intentionally sitting in midst of this complicated reality, letting the complexity simmer. The borderlands have been at a crisis point for a number of years, and the situation is not improving. The political landscape is bleak. And yet, the people I have met over the past few days give me hope for the future. My faith calls me to give voice to the voiceless, and this trip is giving me concrete tools, poignant stories, and real lived experiences that will help me to do so.

I have long believed that the greatest gift that Unitarian Universalism has to offer the world is an ability to inhabit the place of paradox. At our best, we understand that, in the words of Francis David, “We need not think alike to love alike,” and that life is full of paradox. We live our lives together in a complicated web of opinions and beliefs, and we do not expect that we will all agree. And in the midst of that, we figure out a way to live together in peace and harmony. Immigration policy and the reality of life at the border are complicated issues with multiple stakeholders and no easy solutions. We have an opportunity to share our unique perspective and continue to organize and advocate for change.

We were shocked, we were saddened, and we are compelled to tell others about the violation of human rights perpetrated by our government. The economic and political systems of the global north have systematically undermined the livelihoods and survival of the most vulnerable of our neighbors to the south.

We were shocked, we were saddened, and we are compelled to tell others about the violation of human rights perpetrated by our government. The economic and political systems of the global north have systematically undermined the livelihoods and survival of the most vulnerable of our neighbors to the south.