by Deva Jones | Sep 25, 2015 | Environmental Justice, GROW, Young Adult

This post was written by Amelia Diehl and originally posted on Blue Boat.

I am so grateful to have been able to attend the Unitarian Universalist College of Social Justice‘s Grounded and Resilient Organizer’s Workshop Climate Justice Training in Chicago, IL and feel connected again to a community and to a movement. I think I might have learned more about myself and climate change in that weekend at the GROW training than my few years or so of calling myself an environmentalist, and in ways I could never have predicted. The space created for group reflection allowed me to learn a lot about what it means for me to be involved in the movement, and also to forget about myself at times.

Earlier this summer, I interviewed a local climate activist who told me that according to one study, by 2030 we would know if we hit the two degree celsius temperature change, a crucial tipping point. That in fifteen years we would pretty much know how much we were screwed. While these types of doomsday scientific reports circulate regularly and the exact numbers are debatable, somehow hearing it in the context of his personal investment hit me deeper than before. Since that conversation, I’ve felt desperate, frantic and apocalyptic – but also revolutionary, that something big would have to change. I felt a renewed purpose and urgency in my climate work, which until then had felt distanced; I paid attention to news, read Naomi Klein and went to major protests, but didn’t really feel like I could commit as much to the movement as I’d wanted.

About a month later, one of my friends, a woman of color, said she didn’t like the environmental movement. When I asked why, she laughed and said because it’s so white. I agreed, but was frustrated, because even though I was white, I resented the reputation of whiteness in a movement that I know to be more intersectional and that I want to be more explicitly intersectional because it needs to be. I tried to argue that it’s more than protecting trees and water, and that climate change affects us all.

For now, it seems lik![photo1[5]](http://blueboat.blogs.uua.org/files/2015/08/photo15-300x224.jpg) e my front-line is my campus. The brand of environmentalism at our campus – a small liberal arts college in the mid-west – is as white as a blizzard. Our environmental club, though popular, mainly goes on week-long backpacking trips during semester breaks, and lacks a divestment movement. The administration touts sustainability efforts just like the next college, but there is an overall lack of discourse around climate change, and especially around justice. People care about it, sure, but most people get too overwhelmed and feel like we couldn’t do anything about it, or that it isn’t relevant, and often get stuck in “save the Earth” thinking.

e my front-line is my campus. The brand of environmentalism at our campus – a small liberal arts college in the mid-west – is as white as a blizzard. Our environmental club, though popular, mainly goes on week-long backpacking trips during semester breaks, and lacks a divestment movement. The administration touts sustainability efforts just like the next college, but there is an overall lack of discourse around climate change, and especially around justice. People care about it, sure, but most people get too overwhelmed and feel like we couldn’t do anything about it, or that it isn’t relevant, and often get stuck in “save the Earth” thinking.

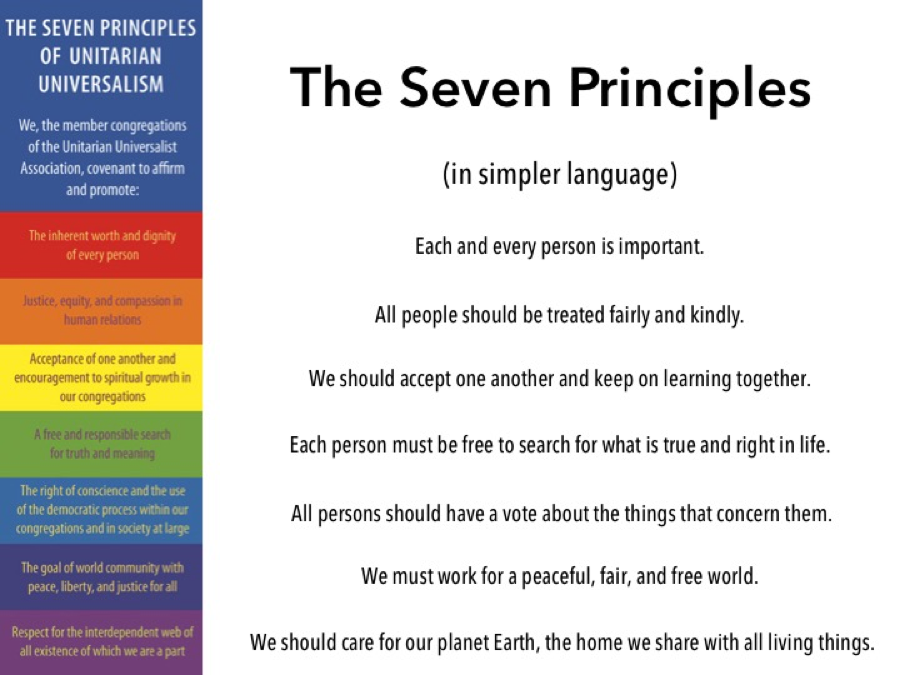

Looking back at when I started to care about environmentalism and climate change about ten years ago, I recognize that my early investment lacked a critical analysis of power systems. Like many Unitarian Universalists in climate work, I resonate deeply with the seventh principle, the interconnectedness of all things. I often envision our planet in space, and think about all of us sharing this home. In a social justice context, this also means that my liberation is tied up into yours. But I don’t think we – as a movement – are there yet, as someone at the training expressed.

One example, among many: a reasonable critique of vegans and vegetarians, many of whom are white (including me), is that they seem to care more about the health and safety of animals than for other people. Changing consumer choices in the context of capitalism is relatively easy compared to critically looking at how I am implicated in a white supremacist (capitalist, patriarchal) society.

I realized that my values of caring about climate change led me to critically look at systems of power and societal inequalities. In other words, I admit that while I cared about social justice in a very white middle class liberal way, it was climate change that got me to understand the complexity and depth of power systems, and my own privilege. To care about climate justice is to care about anti-racism, feminism, anti-capitalism, anti-injustice and anti-oppression, and to fight for liberation. Climate change is only the latest symptom of these oppressive systems. Of course, it is still a choice to engage in anti-oppressive work, and not all climate work means climate justice, and climate justice does not mean simply adding “justice” to the end of it.

It is important to remember and understand each of these anti-oppression movements have different histories and are not the same. Anti-racist work cannot always be lumped with climate justice work. Yet it is crucial to make the connections between the movements.

One of the most impactful parts of the training came after looking at different definitions of climate justice, and one of our facilitators asked us to reflect on how, or if, our goals dismantle the master’s house, and how, or if, our tactics are accountable to the environmental justice principles. I know that this question needs to be considered continuously throughout any work, and I know that the work being done on my campus is not there yet. After the GROW training, I understand more than ever the urgency to challenge this white, privileged environmentalism and bring in a climate justice framework, and, importantly, I feel more prepared to do so.

I am determined to bring this awareness and analysis back to my campus. We’ll still go backpacking, and I will make sure we talk about the master’s house in the context of climate justice principles. I suspect many a college campus are stuck in white environmentalism, though many have been struggling for divestment from fossil fuels. I also want to start a divestment campaign, though this feels like a lofty goal at this point for where my campus’s values lie.

I know that this awareness is not enough, that there must be action. Yet it is a concrete step forward, and I know I will keep learning. As a participant said, we are responsible for collective learning.

Along with organizing skills, the GROW training gave me a space to truly examine and express my despair over climate change, the deep kind I felt at the beginning of the summer. It is easy to become fixated on the dystopian projections of extinction – of other species and possibly our own – destruction, and loss of the life we are used to, and to focus on climate change as an urgent crisis. Yet the problem with this is that this apocalypse has been real and remains urgent for so many for centuries. It is not about oppression olympics, or a hierarchy of despair, but it is about urgency.

The face of the climate movement may still be very white. Yet the crucial part is making sure front-line communities take the lead, and that those with privilege take the time to critically examine their positionality, and remain accountable to climate justice principles. As a facilitator said, we need to struggle together and resist collapses, and it’s up to us if there’s to be justice on the other side.

Amelia studies Environmental Communication and Arts at Beloit College in Wisconsin. Originally Quaker, she joined her local UU congregation in high school. She’s interested in how art is used in social movements, and in particular writing and photography. In addition to her environmental activism, she leads an interfaith student group organized for incarceration justice.

by Deva Jones | Aug 5, 2015 | Internship, Young Adult

This post was written by one of our 2015 interns, Carter Smith, and was originally published on Standing on the Side of Love’s website here.

Unitarian Universalism is in my blood. I am here today because my parents met at the UU church in Birmingham, Alabama many years ago when they were seeking spiritual community in young adulthood. Despite growing up within UUism, I feel like my faith is very deliberate and was truly formed by my involvement in my home church in Chapel Hill, North Carolina throughout high school. One day my minister mentioned to me a program for youth involved in social justice in Boston. This would turn out to be the inaugural Activate Justice Training of the UU College of Social Justice. So, I went to Boston and was exposed to this faith organization on a national level for the first time while I solidified my commitment to social justice. Also, I met an intern they were hosting and I made a note in the back of my head to remember that as an option when I became a college student. Three years later, after my first year studying religion and political science at UNC Asheville, it seemed like the perfect fit, so I applied and was placed with our Standing on the Side of Love campaign in the UUA’s Washington DC office.

Before I began the application process, I had a personal connection with Standing on the Side of Love, as my home church had been very involved in the campaign. In 2012, North Carolina had an initiative on our primary ballot that supported adding an amendment declaring the already banned same-sex marriage to be unconstitutional. Our Standing on the Side of Love committee organized phone banks multiple times a week, where I was able to help coordinate and train volunteers. While the initiative did pass, I grew my passion for love activism and learned the power of a group of people acting for justice. Standing on the side of love became a truly radical idea.

It only seemed fitting that the US Supreme Court would make the landmark decision legalizing same-sex marriage in all fifty states while I was a staffer at Standing on the Side of Love. I had the opportunity to celebrate this decision alongside thousands of other Unitarian Universalists at this year’s General Assembly. While reveling in this victory, we also created space to grieve the massacre at the Emmanuel AME church and the continuing personal and structural violence towards people based on race, gender identity, sexual orientation and immigration status. And we must respond, by standing in solidarity with communities that fighting for their human rights to be respected. When I traveled to Winston Salem, North Carolina for the Mass Moral Voting Rights March, I became acutely aware of this tipping point in history that I have the opportunity to be a force for good in. These specific events during my time in this internship have made it so clear to me that there is no place to be except for on the side of love.

In truth, most of my time here has been spent in a cozy office, sending emails, editing blog posts and attending conference calls. These have not been the most riveting assignments of my internship, but I can say that I have grown an immense appreciation for the day to day tasks of running a justice campaign. When hundreds of Unitarian Universalists show up at a march, or churches across the country come together to offer a weekend of same-sex marriages, it is a direct result of hard work and organizing done at a desk. Standing on the Side of Love is strong because of the great leaders at the Unitarian Universalist Association who offer their justice and creative expertise. I am so grateful that I have gotten a glimpse of the insight and skills that it takes to do the behind the scenes work that make powerful justice events possible. Whatever I may go on to do with my life, I will carry with me a stronger commitment to justice as well as the tools to respond to those issues surrounding our lives.

The most valuable education I feel that I’ve gotten has been on the specific issues that we face in the justice community. Working at Standing on the Side of Love has renewed my commitment to pursuing justice- I see that I have the power to start conversations and organize in my own communities. And, I invite you to do the same. Take the leap from conviction to action; find out about organizations to get involved with in your area and be part of the conversation. As I wind down this internship experience, I have one request for you: find the ways to deepen your commitment to social justice and your faith. One immediate way to show up for love is to join with other UUs in Ferguson this weekend to commemorate the anniversary of Michael Brown’s extrajudicial killing. History is happening now and we can be a force for good by speaking up and showing up on the side of love.

In Faith,

Carter Smith

Standing on the Side of Love/UU College of Social Justice Summer Intern

Student, University of North Carolina Asheville

by Deva Jones | Nov 24, 2014 | Internship, Young Adult

This post was written by Eleanor Brow, a participant in the Global Justice Summer Internships.

Coming out of my freshman year of college in May 2014, I felt even more confused about what I wanted to do with my life than when I began college back in August. I had gone to many events and participated in a lot of clubs throughout the year, but choosing one career or subject and then following that forever seemed so daunting and scary. I go to American University (AU) in Washington, DC where life is very different compared to my small hometown in North Carolina. Everyone at AU wants to change the world or be the President one day. These goals are amazing and people should strive for them, but are they right for me? What do I want to do? How will I seize my future? These were new questions that I now had to deal with.

I knew jumping into an internship would be very beneficial to me. I hoped learning professional skills would help for my future and help me solidify what type of work I wanted to be apart of when I did graduate. I was raised Unitarian Universalist and always loved connecting with UU’s when I was in high school. Through the UU College of Social Justice, I found an internship with Standing on the Side of Love. I felt interning here for the summer would be the perfect opportunity for me in my current state of limbo. Working in an office on social justice issues definitely seemed like the place that would help me answer some of the questions I currently faced.

As I reflect on my summer internship at Standing on the Side of Love, I am confident I have learned important skills in which I will use in my future endeavors. This internship was a very rewarding experience in which I received firsthand experience at how a public advocacy campaign actually functions. I worked professionally with my supervisors on outreach to the general public and UU communities on topics such as gay rights, immigration reform, and religious rights. I have become skilled in many social media platforms, WordPress, and SalsaLabs, and basic HTML coding.

My internship was not exclusively just in the UUA DC office. A lot of my work took place out in the city of DC as well as in Boston and Providence. These tasks included advocating for Congress to pass comprehensive immigration reform, attending panels on the Transgender rights movement, participating in the Multicultural Growth and Witness Retreat, rallying for immigrant right at the White House, and staffing General Assembly 2014 in Providence, RI.

Being a part of General Assembly was definitely the most rewarding part of my internship. Preparing for GA was very stressful since we had a lot to do for Standing on the Side of Love’s 5th year Anniversary at this year’s GA. We all put so much work into preparation and then seeing all our work pay off in successful events at GA was amazing for me to see.

This internship has dramatically altered my views for my future and I am so thankful for the lessons it has taught me. I’ve learned so much in an incredibly short time. This internship gave me the opportunity to see what being a real working human being is like and how to maintain a countrywide movement around the amazing concept of love. I have become more aware and educated about social justice issues. I now feel so inspired to pursue social justice work at other organizations in Washington, D.C. and will continue to be involved and fight for people’s basic human rights. I also feel recommitted to Unitarian Universalism and want to continue attending All Souls Church in DC and stay connected with local UU individuals. I am thankful to my supervisors and colleagues in the DC office along with the amazing staff I have encountered in Boston. It has been an amazing summer and I look forward to the future.

by Deva Jones | Oct 10, 2014 | Economic Justice, Internship, Young Adult

This post was written by Renee Bryant, a participant in the Global Justice Summer Internships.

Working with Jose Oliva this summer at the Food Chain Worker’s Alliance (FCWA) allowed me the opportunity to reflect on my previous experience as a black woman in the food industry and study more about food justice overall. Jose is a Latino male and has worked in the food industry in the past. His experience is what drives him and gives him a passion to highlight the injustice, specifically in the form of pay that workers in the food industry receive. Women and racial minorities are consistently at the bottom of the totem pole when it comes to food industry justice because they are often in positions where they can be taken advantage of due to the hierarchies and systems our society sustains to keep those groups at the bottom. From working with Jose, I learned that these people often cannot afford an education and are stuck working dead-end food jobs where they get paid little and work long hours. Over time it becomes a cycle and these people get stuck in sometimes multiple food jobs struggling to make ends meet while the companies they work for make billions.

I could identify with the little pay and exhausting work due to my experience working at McDonald’s one summer. The summer after my freshman year of college I had not gotten any internship offers so I took a job at my local McDonald’s as an overnight crew-member. I do not come from a privileged background and I needed money for books and other expenses since Vassar is not exactly a cheap school. I worked four or five nights a week and made $7.25 an hour. My duties included cleaning the restaurant, taking orders, cashier, and stock for the next day. By the time 6 a.m. rolled around my feet would be sore, I was annoyed from being sexually harassed by customers and coworkers all night, and sad I was missing the summer fun all my friends were having. When I would turn in my drawer, I would notice how much money the restaurant was making and compared that to how little I was receiving in my paycheck.

Fortunately for me, the job was only temporary and I was able to return to school and move on. Some of my coworkers did not have the privilege of a short experience and for them McDonald’s was their sole income. I could not imagine trying to raise a family or live on my own on the wages a McDonald’s salary provides because the money I made during the summer barely covered the cost for my books and incidentals for the first semester. In some ways feel like there is some disconnect from me and the other employees despite the fact that I am a woman of color and a lot of my coworkers fit into that demographic. I at least had the luxury of moving on to work on my education while others could not even afford community college. Pairing my experience at McDonald’s and my experience at FCWA has shown me that everyone deserves to get paid a fare wage whether they are only a college kid making summer money or a single mom with a teenage son. The lesson I learned this summer at FCWA was that every job and every worker is worth more than companies are willing to admit.

![photo1[5]](http://blueboat.blogs.uua.org/files/2015/08/photo15-300x224.jpg) e my front-line is my campus. The brand of environmentalism at our campus – a small liberal arts college in the mid-west – is as white as a blizzard. Our environmental club, though popular, mainly goes on week-long backpacking trips during semester breaks, and lacks a divestment movement. The administration touts sustainability efforts just like the next college, but there is an overall lack of discourse around climate change, and especially around justice. People care about it, sure, but most people get too overwhelmed and feel like we couldn’t do anything about it, or that it isn’t relevant, and often get stuck in “save the Earth” thinking.

e my front-line is my campus. The brand of environmentalism at our campus – a small liberal arts college in the mid-west – is as white as a blizzard. Our environmental club, though popular, mainly goes on week-long backpacking trips during semester breaks, and lacks a divestment movement. The administration touts sustainability efforts just like the next college, but there is an overall lack of discourse around climate change, and especially around justice. People care about it, sure, but most people get too overwhelmed and feel like we couldn’t do anything about it, or that it isn’t relevant, and often get stuck in “save the Earth” thinking.